The region is increasingly vulnerable to disasters.

SCROLL TO LEARN MORE

SCROLL TO LEARN MORE

Climate change is a threat that our coastal region is only starting to grapple with.

Even if we aggressively reduce our carbon emissions, sea levels are projected to rise at least six inches by 2050, and the damage caused by storms is expected to rise 30% by 2100.

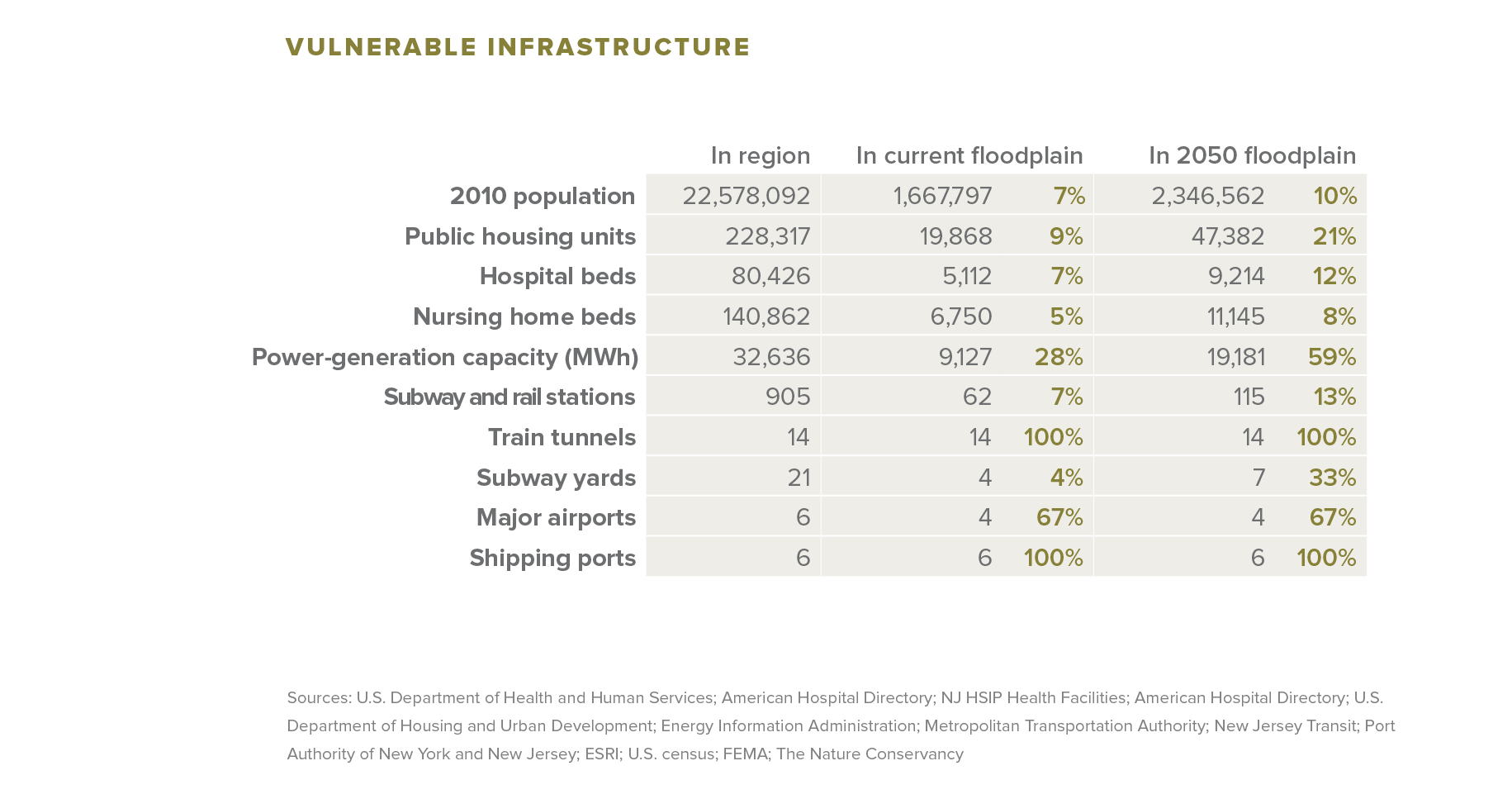

People continue to move into areas prone to flooding. In fact, since 1990, when the first Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report was published, the population in the area at risk of flooding has grown by 200,000, reaching 1.67 million people region-wide. By 2050, 2.3 million people are expected to be living in areas of the tri-state region that are at risk of flooding.

Some of the region’s most critical infrastructure is located in areas that flood.

Today, 28% of our energy-generating capacity is located in areas that have a 1% chance of flooding in any given year. By 2050, 59% of our energy capacity will be in areas prone to flooding, as will all of the region’s shipping ports, four of our major airports, 21% of our public housing units and 12% of our hospital beds.

Climate change is just one of the threats we face. Growing reliance on complex technology also increases the risks of system failure.

Because our economy and society are increasingly dependent on computers, we are more vulnerable to disruption of computer-based services. One glitch can cause disruptions all the way down the chain. The primary cause of the Northeast blackout of 2003 was a bug in energy management software. In 2013, it was a computer problem that shut down the Nasdaq Stock Market for three hours. And in an increasingly integrated global economy, millions of dollars can be lost when systems are down for just a short while.

The risk of any kind of disruption is compounded by private industries adopting lean supply chains.

Under pressure to reduce costs, the production and distribution systems in a range of industries – from fuel to food to consumer products – have been modified to minimize unused inventory. But when an event disrupts this tightly controlled “just-in-time” arrangement, supply chains fail. After Hurricane Sandy, for example, it took days for food to return to grocery store shelves. Warehouses held little inventory, and storm-related road closures prevented them from restocking food that had been grown hundreds of miles away. The transportation problem was compounded by widespread disruptions to the gasoline supply, an industry that also has adopted just-in-time inventory management.

Aging infrastructure and decades of underinvestment heighten the risk of catastrophic events.

From water and sewer pipes, to power networks to transportation systems, much of our infrastructure was built a century ago. Lack of investment has led to frequent failures.

On Metro-North, four passengers were killed when a train derailed around a sharp curve that lacked a common safety measure. An electrical outage a few months earlier disrupted service for more than two weeks.

Eight people died and 70 were hurt when two East Harlem buildings collapsed in March 2014. A leak in a century-old cast-iron gas main was found nearby.

A string of breaks on aging water mains last year in Hoboken flooded basements and left much of the city without water.

Trains are regularly delayed by backups in and out of the antiquated trans-Hudson rail tunnels, which frequently need repair. And if one of the tunnels failed, the consequences would ripple across the region for days, weeks or even months.

*An earlier version of the vulnerable infrastructure map gave the incorrect share of public housing units in the 2050 floodplain. The correct figure is 21%. Also, an earlier version of the map included Peninsula Hospital Center in the Rockaways. The center closed in 2012.